Recently, the terms agroecology and agroecological have been springing up more and more in different contexts. But what is agroecology? And why is it so tricky to define? If you’ve been a bit confused about the meaning of agroecology then don’t worry, you’re not the only one.

After I wrote this blogpost, Landworkers’ Alliance in collaboration with FLAME and film maker Joya Berrow made this excellent short film – “What is Agroecology?”. This seemed like a better place to start and I’ve left more detail and references on the agroecology below.

So, let’s start from the ground up. First, it’s helpful to define ecology. Ecology is the study of the interactions between living things and the environments they are in1. A good starting definition of agroecology then, is the ecology of food systems2. In a broad sense, this involves understanding the interactions between living organisms (including humans) and their wider contexts in the food system. But we need to dig deeper to understand what that really means in practice and root out the different interpretations of agroecology or “agroecologies”3 that are sometimes in conflict with each other.

There are several reasons for the confusion over the term agroecology:

- Agroecology is generally accepted to have three forms: science, practice and movement4. Some people consider all of these three forms as integrated. Whereas others try to detach the ecological study of agriculture or the practice of sustainable agriculture (based on agroecological principles) from their connection to rural social movements.

- Agroecology has developed differently in different countries based on their historical, social, political and cultural contexts. This also relates to which of the three approaches (science, practice, or movement) is more dominant in each place. In Latin America, for instance, there is a strong history of agroecology in social movements and peasant organising. Even in Latin American scientific research, the roots of agroecology are seen as coming from traditional peasant and indigenous practices. This is very different to Germany where some of the earliest agroecological research was carried out and a scientific understanding is more central.

- Agroecology has been used to refer to different scales. Earlier in its development as a science it often referred just to the plot or field-scale and understanding the ecological interactions there. From the 1970s, the term started to be expanding to understanding the whole farm system or ‘agroecosystem’ and consider not just biological interactions but also the social and cultural context of a farm and farmers. From the 2000s, it became more common to think of agroecology as involving the whole food system.

- Agroecology is a contested term5. Whenever you see the term agroecology it’s important to uncover the narratives that are being associated to it because it is not always clear. Depending on the political views and interests that different groups have they will frame agroecology differently. A government or large institution might contextualise agroecology in a very different way to an NGO or social movement, using different language and either including or excluding certain aspects such as social and cultural dimensions of food systems. There are growing tensions around the use of the term. Groups such as peasant movements, civil society organisations and allied academics want to defend the transformative potential of agroecology and ensure it isn’t used in a way that maintains the unequal relationships and harmful impacts of the existing food system.

Agroecology as science

The science part is the natural and social scientific study of agroecosystems and/or food systems which began earlier in the 20th century with the meeting of the fields of ecology and agronomy6. Since then it has expanded to encompass many disciplines and look at the cultural, social and political aspects of agriculture beyond the field level. It is often associated with transdisciplinary research, that is, academics and non-academics engaging in participatory processes to explore issues from a number of different viewpoints and ways of knowing. This kind of research involves collaboration between scientists, farmers, technicians, activists and NGOs to develop research that is defined by the needs of producers and citizens7.

Agroecology as practice

The practice part refers to the sets of practices developed in different places which are guided by ecological principles and promote sustainable rural development. This is often presented in opposition to industrial modernist practices that have grown to dominate agricultural research and practice since the 1950s. Instead of monocultures, agrichemical inputs, transnational markets and GMOs, agroecologists tend to promote crop diversity and biodiversity, water and soil management, local food economies, seed saving, and reducing reliance on external inputs. Since an agroecological approach pays attention to interactions of living things with their environment, there is no set of universal practices but instead diverse variation of context-dependent practices. This means drawing upon traditional local and indigenous knowledge and understanding the complex interactions in a given area including native plant species and soil biology. This also means embedding ecological and technical practices within the cultural, social and spiritual practices that are relevant to the specific places and those involved in managing agroecosystems8.

Agroecology as movement

“Agroecology is understood in popular movements as the recovery of ancestral knowledge associated with food production, as well as access to the productive means needed for this knowledge to contribute to the collective right to build and defend food systems, a right also known as food sovereignty.”9

Agroecology as a rural social movement has its roots in Latin America where it was first linked to the concept of food sovereignty. Over time, social movements in the global North concerned with the environment and globalisation have been influenced by the struggles of peasants in Latin America and elsewhere in the global South through networks such as transnational peasant movement La Via Campesina. A global movement has grown to promote agroecological approaches to the food system, defending territories and peoples from explotation and extraction and recovering local and traditional knowledge and ‘agri-cultures’.

Are you an agroecologist?

We choose to engage with the broader definition of “agroecologists” that Rosset and Altieri use in their book Agroecology: Science and Politics10 as “people who study and/or promote agroecology and the agroecological transformation of farming and food systems, be they academics, researchers, extensionists, activists, advocates and/or farmers, peasants or consumers, including their leaders”.

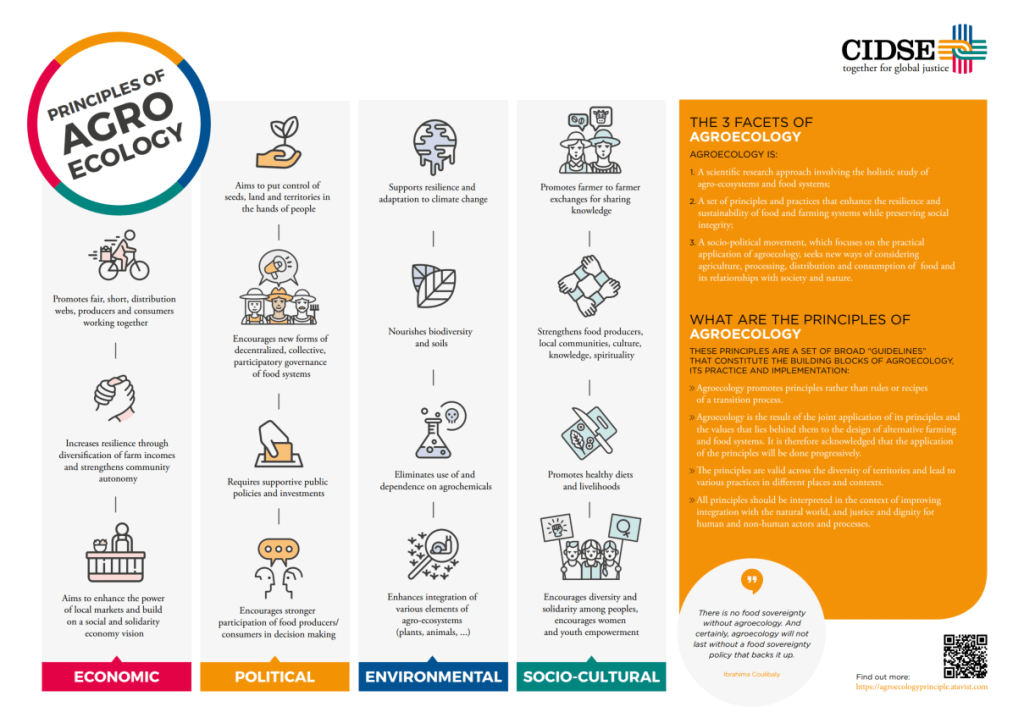

Dimensions and Principles of Agroecology

As mentioned before, understanding agroecology as the ecology of food systems means focusing on more than just the environmental aspects of agriculture. Agroecology is multi-dimensional. It involves the integration of environmental, social and cultural, political, and economic dimensions of food systems. There is a lot of work already out there explaining the principles that guide a transformative agroecology. Here, I’ve chosen an infographic from CIDSE11 which does well to outline the broad principles of agroecology across these different dimensions and from a food sovereignty perspective.

What is the agroecology of Resisting, Learning, Growing?

Most simply, our agroecology is one that: aligns with food sovereignty; addresses issues of justice and sustainability across the food system; seeks a diversity of approaches that are embedded in place and territories; involves a research approach which is transdisciplinary, participatory and action-oriented; and recognises the roots of agroecology in peasant and indigenous knowledge systems and Latin American social movements. We are inspired by a critical Latin American agroecology and the agroecology promoted by international peasant network La Via Campesina. We’re interested in how the values and ideas of this transformative agroecology can be understood in a UK context.

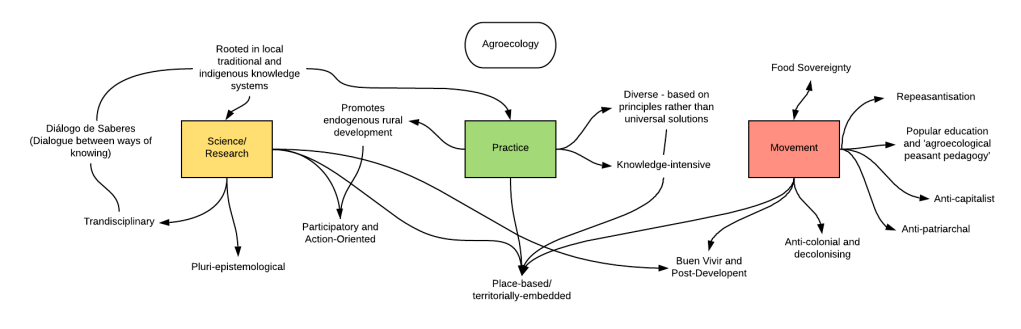

If you are interested in some of the broader concepts that are connected with this food sovereignty vision of agroecology then check out the diagram below. It charts the initial exploration of concepts and theories associated with agroecology for the research project. I am hoping to create more posts like this to share readings and reflections on these ideas as the research develops.

1 https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/about/what-is-ecology/

2 Francis, C., Lieblein, G., Gliessman, S., Breland, T. A., Creamer, N., Harwood, R., Salomonsson, L., Helenius, J., Rickerl, D., Salvador, R., Wiedenhoeft, M., Simmons, S., Allen, P., Altieri, M., Flora, C., & Poincelot, R. (2003). Agroecology: The Ecology of Food Systems. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 22(3), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v22n03_10

3 Méndez, V. E., Bacon, C. M., & Cohen, R. (2013). Agroecology as a Transdisciplinary, Participatory, and Action-Oriented Approach. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 37(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2012.736926

4 Wezel, A., Bellon, S., Doré, T., Francis, C., Vallod, D., & David, C. (2009). Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 29(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009004

5 Giraldo, O. F., & Rosset, P. M. (2018). Agroecology as a territory in dispute: Between institutionality and social movements. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(3), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1353496

6 Gliessman, S. R. (2014). Agroecology: The Ecology of Sustainable Food Systems, Third Edition (3 edition). CRC Press.

7 Levidow, L., Pimbert, M., & Vanloqueren, G. (2014). Agroecological Research: Conforming—or Transforming the Dominant Agro-Food Regime? Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 38(10), 1127–1155. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2014.951459

8 Anderson, C., Pimbert, M., & Kiss, C. (2015). Building, Defending and Strengthening Agroecology: A Global Struggle for Food Sovereignty. ILEIA, Centre for Learning on Sustainable Agriculture and CAWR, Centre for Agroecology and Resilience.

9 Rosset, P. M., Barbosa, L. P., Val, V., & McCune, N. (2020). Pensamiento Latinoamericano Agroecológico: The emergence of a critical Latin American agroecology? Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 0(0), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2020.1789908

10 Rosset, P. M., & Altieri, M. A. (2017). Agroecology: Science and Politics. Practical Action Publishing.

11 https://www.cidse.org/2018/04/03/the-principles-of-agroecology/